In his book Invasion! published at the end of 1944, journalist Charles Christian Wertenbaker gave a first-hand account of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, which he covered at the side of Robert Capa (1913-1954). Assigned with four colleagues to cover the D-Day landings with American troops, the Hungarian photographer began by documenting the preparations and the boat journey to the beach. Wertenbaker related his friend’s experience: “I was on this nice, clean ship with the 16th Infantry. The food is good, and we played poker most of the night, and once I filled an inside straight, but I had four nines against me, which was not unusual.”

Dawn was breaking, the armada was approaching Omaha Beach. Capa described the situation, again with a sense of humor: “Just before 6 o’clock, we were lowered into our LCPV and started for the beach. It was rough and some of the boys were politely puking into paper bags and I saw that this was a civilized invasion. We waited for the first wave [the special assault teams] to go in and then I saw the first landing boats coming back and the black coxswain of one boat [was] holding his thumb in the air and it looked like a pushover. We hear[d] something popping around our boat, but nobody paid any attention. We got out of the boat and started wading. Then I saw men falling and I had to push past their bodies, which I did politely, and I said to myself ‘Mon vieux, this is not so good’.”

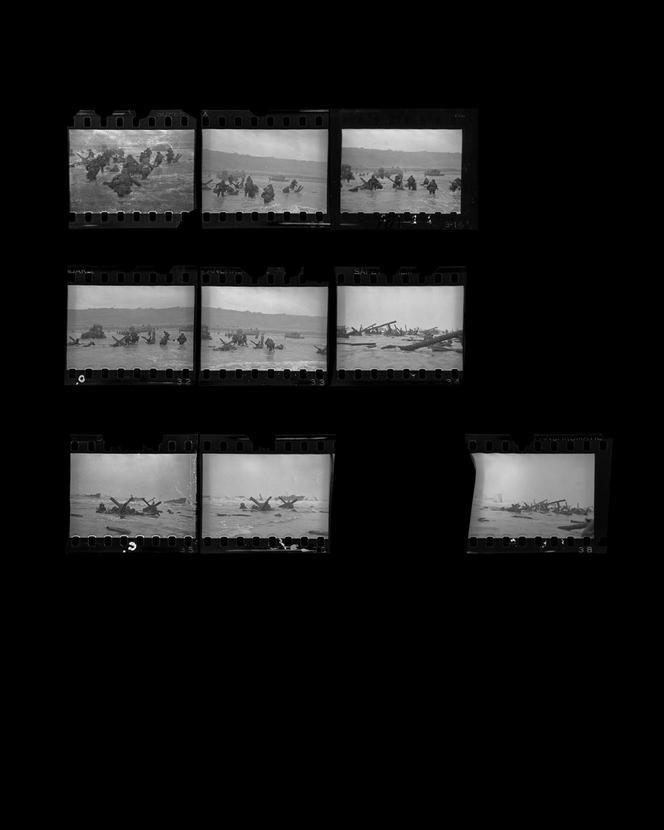

Eleven slightly blurred shots

He took photos with one or other of the two Contaxes he carried around his neck. He photographed the soldiers getting out of the barge and jumping into the water, followed them, then turned around and photographed the unfortunate men trying to get a foothold on the beach. The sea was red with blood, corpses floating, blown apart by German machine guns. In his autobiography, Capa described: “After twenty minutes, I suddenly realize that this is not a good place to be. The tanks were a certain amount of cover from small arms fire, but the were what the Germans are shooting shells at. So I made for the beach. I fell down next to a soldier who looked at me and said: ‘This is harder than sweating out an inside straight.’ Antoher soldier looked up ans said: ‘I see my old mother sitting on the porch waving my insurance policy.’ It was very unpleasant there and having nothing else to do, I start shotting pictures. I shoot for an hour and a half, and then my all my film is used up.”

He unsuccessfully attempted to change the film, then climbed back into a barge. He had his scoop. He had to get back to the boat to return to England and send the reels to London, which would transmit them on to New York. He then returned to France on another boat. From there on, the prevailing version is that of John Morris of Life magazine, who received the film rolls. Three or four rolls arrived, and they had to be hurried to New York to the newspaper’s editorial office, where they would be published on June 19. Unfortunately, most of the negatives were destroyed by the heat in the drying cupboard, and only 11 photos, “The Magnificent Eleven,” were usable. Only nine remain today.

You have 18.68% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.