In JANUARY 2010, when Boa Sr passed away at 85, with her, humanity lost the Great Andamanese language of ‘Aka-Bo’ that was also said to be used by the Bo indigenous community to communicate with the birds. Boa Sr was the last speaker of the now extinct language. “This ancient communication system existed as a common thread between two different species but now we have lost that link,” says artist Manish Pushkale.

Introduced to Aka-Bo during a lecture by literary scholar-activist Ganesh N Devy in 2019, Pushkale lamented the loss and deliberated how the extinct language could be translated into visuals. “I use it as a metaphor for lost treasure, a warning. How can we justify this linguistic loss? The world is reaching a monolingual cacophony. In the digital age, our communication might be faster, but there is erosion of human emotions, gestures, our collective ancestral memories and traditions such as calligraphy,” says the Delhi-based artist.

The contemplations led to several inquiries, resulting in the show “To Whom the Bird Should Speak?”. Exhibited at Musée Guimet in Paris last year, it is currently on view at Musée des Arts Asiatiques in Nice, France. Presented on a maze of three-metre screens, viewers are invited to wander through the 60 paintings that comprise the labyrinthine folio where the only recognizable forms are the moon and an image of a bird. “Through it, I am attempting to recreate lost scripts and languages, using an imaginary archive of languages,” says Pushkale, 50. It took him several years to develop the visual vocabulary — from preparing preliminary drawings to making his own surface for the paintings. , reading texts on Aka-Bo and referring to inscriptions in ancient languages such as Prakrit and Brahmi and the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The groundwork also entailed traveling through different states, from Andaman to Bastar in Chhattisgarh, and the Bhimbetka caves and Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh. He would carry back found materials such as sand, soil and charcoal, which inspired the textural paintings, serving as symbols for the bygone times. “For instance, I have extracted black from the basalt rocks of Madhya Pradesh,” says Pushkale. He recalls how as a nine-year-old he first created his own language and script. “It was a game of sorts but probably the beginning,” he adds. XX Born in Bhopal to parents working in the public sector, he notes how his initial exposure to art was through family outings to archaeological sites.

While a sign-board painter in his neighborhood introduced him to the skill, the opening of Bharat Bhavan in 1982 gave the exposure and impetus required for the young boy to discover the language of colour. “I started bunking classes in school and college to visit Bharat Bhavan. Fascinated by the artworks, I would observe how each artist had his own style, techniques. Back home, I would practice on my own,” recalls the autodidact. Soon, he began interacting with artists visiting the museum, including J Swaminathan, Manjit Bawa and Jangarh Shyam. Art conservator Rupika Chawla encouraged the postgraduate in geology to join a course in restoration and conservation at Delhi’s National Museum. “At first, my family wasn’t too keen on me pursuing art as they were not sure about the future prospects but they eventually came around… The course also gave me a window to understanding how material behaves,” recalls Pushkale.

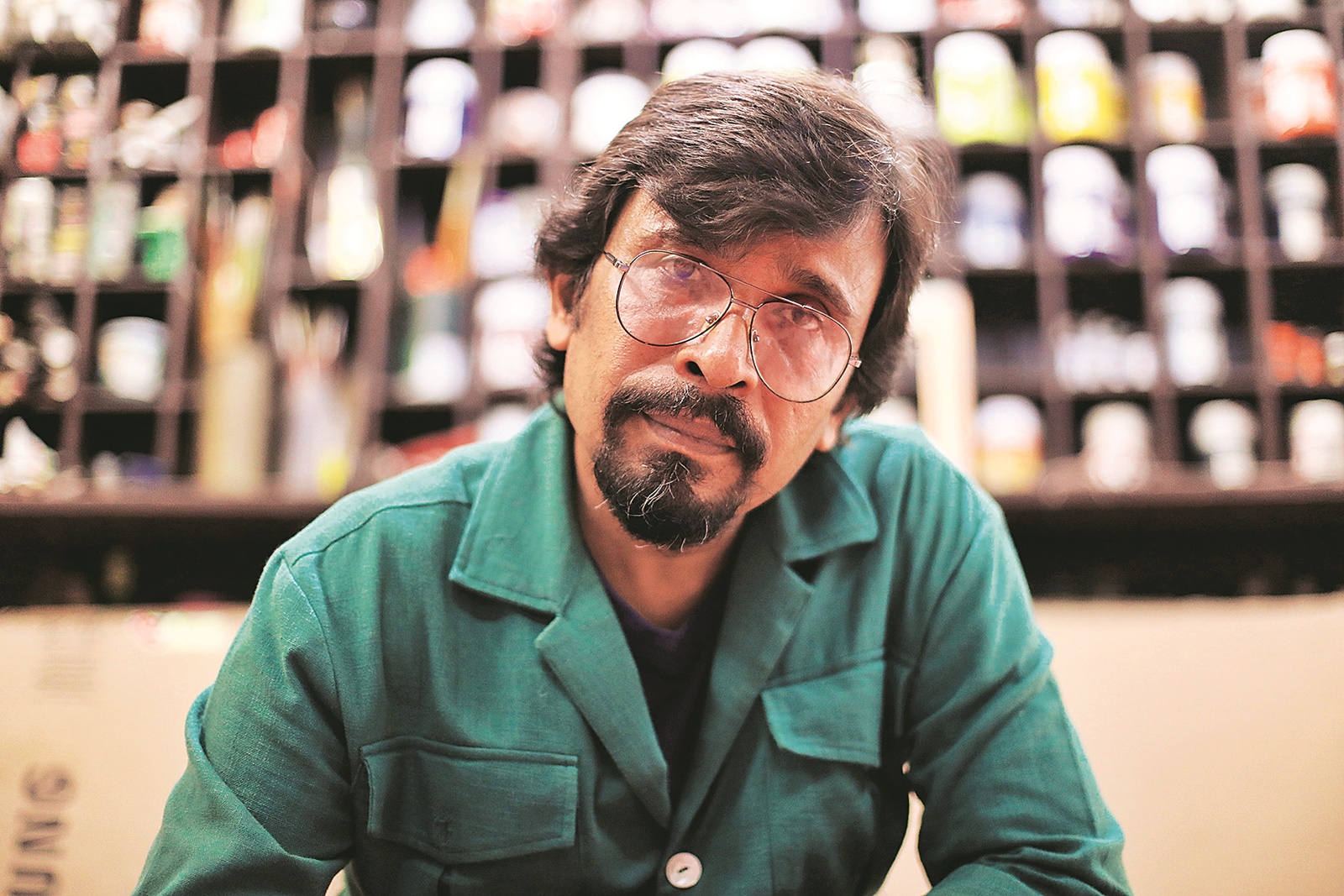

Artist Manish Pushkale at his residence in Hauz Khas in New Delhi on Tuesday, July 02, 2024. Express photo by Abhinav Saha

Artist Manish Pushkale at his residence in Hauz Khas in New Delhi on Tuesday, July 02, 2024. Express photo by Abhinav Saha

Arriving in the Capital with Rs 16 and admission at National Museum in the mid ’90s, Pushkale initially took up part-time assignments, including working on daily wages at excavation sites of the Archaeological Survey of India. Also continuing his art practice, although his initial engagements were figurative, soon he turned towards more abstract renderings. Delhi also opened a new world, as he now frequented museums and galleries and came into contact with artists and writers such as Nirmal Verma and Krishna Sobti. Introduced to SH Raza in 1998, when the modernist was on a trip to India, his works caught the veteran’s attention and he recommended him for a residency in Maison de L’Inde in Paris in 2002. In 2003, the two exhibited together at The Guild gallery in Mumbai.

The same year, Pushkale also had his solo at Gallery Espace in Delhi. Since then, he has exhibited at prestigious venues across the globe, often re-discovering the past as he engages with the present to ponder over the future. If his 2015 exhibition “Museum of Unknown Memories” at Akar Prakar in Delhi, used water from different countries – including Volga in Russia and Ganga in India — to mix color in the palette, his 2023 exhibition “Consistent (in) Consistency” in Kolkata emphasized on embracing diversities. Influenced by his studies of topographical maps and technical drawings, often weaving his layered narratives together are dots, lines and fine kantha stitches.

A detail from the show that presents the kantha stitch (Photos courtesy (for the art): Akar Prakar Gallery and Manish Pushkale)

A detail from the show that presents the kantha stitch (Photos courtesy (for the art): Akar Prakar Gallery and Manish Pushkale)

“People across the world relate with stitches — those from Bengal might associate it as kantha, but for others in France it denotes a technique they are familiar with,” says Pushkale. Recently back in Delhi after working on an installation at a university campus in Gwalior, he notes how his installation in Nice is prompting the audience to ruminate in silence. “Many are intrigued about the existence of this language, as well as concerned about the constantly changing landscape,” he adds.