Picture this: it’s 3000 BC, and along the Indus River Valley people are weaving magic. Not spells, but something just as captivating – cotton! India’s relationship with textiles began way back then, a story told thread by thread. Imagine the soft caress of muslin, so fine it could be mistaken for a summer breeze. Fast forward a couple thousand years, and silk arrives, like a shimmering new chapter. Emperors like the Mughals couldn’t resist adding their sparkle, introducing dyeing techniques that rivaled any sunset and clothes embroidered with literal gold ‘tars’ like zardozi.

For those of you fascinated by this layered legacy, we bring a new series on Indian textiles to quench your thirst. From the history of a textile to its legacy and what can be done to revitalize it, along with identifying a ‘fake’, we have the answer to all your questions.

The first dispatch in this series begins with zardozi.

This elaborate metallic embroidery is done on different kinds of fabrics such as silk, brocade, velvet satin and georgette. (Source: Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla)

This elaborate metallic embroidery is done on different kinds of fabrics such as silk, brocade, velvet satin and georgette. (Source: Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla)

From the Rig Veda to Mughal opulence: The history of zardozi

Zardozi’s story is an epic in itself that intertwines with India’s textile heritage. Although many believe it came to India through Persia, according to Professor John Varghese, School of Fashion, World University of Design (WUD), the origins of this art can be traced back to the time of the Rig Veda. “It flourished during the reign of Mughal Emperor Akbar, bringing with it Persian influences evident in today’s motifs, materials, and naming conventions,” he said.

The word “zardozi” itself whispers of its Persian influences, with ‘zar’ meaning gold and ‘dozi’ meaning embroidery in the language, literally translating to “embroidery with gold,” explained designer duo Abu Jani-Sandeep Khosla, who have extensively worked with the textile over the years.

This elaborate metallic embroidery is done on different kinds of fabrics such as silk, brocade, velvet satin and georgette. According to Abu and Sandeep, emperor Akbar patronized and popularized zardozi as regal attire for kings, queens, royalty and the nobility in India.

“Zardozi designs essayed exquisite flora and fauna and were created using gold and silver threads and also employed pearls, beads, sequins, as well as precious stones. Historically, zardozi embroidery was used to adorn the walls of royal tents, courtrooms, scabbards, wall hangings and the paraphernalia of regal horses and elephants,” they told indianexpress.com.

Originally the zardoz crafters used pearls and precious stones, setting them with real gold and silver thread, explained Sanya Dhir of Diwani Couture, dedicated to revitalizing the art.

That is how this embroidery technique became synonymous with luxury and prestige, adorning the attire of emperors and nobles, says designer Archana Jaju, adding that over time, zardozi evolved, adapting to changing tastes and embracing new materials and motifs.

How is zardozi made; What are the challenges?

Zardozi embroidery is a labor-intensive process that involves intricate craftsmanship and attention to detail. The process typically begins with the selection of a design, which is then transferred onto the fabric using a temporary marking method such as chalk or water-soluble ink.

Next, skilled artisans, known as karigars, Meticulously embroider the design using a variety of techniques. They start by outlining the design using a fine needle and metallic thread, usually gold or silver. This outline serves as the foundation for the intricate embellishments that follow. The embellishment process involves filling in the design with metallic threads, beads, sequins, and sometimes even precious stones. The karigars use specialized stitches such as the satin stitch, chain stitch, and couching to create texture and depth in the embroidery.

Throughout the process, the karigars work with precision and patience, carefully layering each element to achieve the desired effect. Depending on the complexity of the design and the size of the piece, zardozi embroidery can take anywhere from several days to several months to complete. Larger or more elaborate pieces may require a team of artisans working together to finish the embroidery in a timely manner.

Mastering the techniques takes time and practice (Source: The Zardos Project, Diwani Couture)

Mastering the techniques takes time and practice (Source: The Zardos Project, Diwani Couture)

According to Jaju, one of the main challenges with zardozi is the level of skill and patience required. “It’s a highly intricate art form that demands precision and attention to detail. Mastering the techniques takes time and practice,” she says.

Additionally, working with metallic threads and delicate materials can be challenging, Jaju added, as they require careful handling to avoid breakage or damage. “Sourcing high-quality materials can sometimes be difficult, especially if you’re aiming for authenticity and excellence in your work. Despite these challenges, the beauty and cultural significance of zardozi make it a rewarding art form to pursue.”

A delicate thread threatened: How do you spot fake zardozi?

According to Abu-Sandeep who began their design journey in the 80s, the times “were depressing and the market was flooded with cheap zardozi that lacked all finesse and imagination.” Talking to this outlet, they noted how difficult their beginning were because of fake zardozi in the market.

“The clumsy, crude, uninspired stitches had reduced a once regal craft to the common place. We were a part of the movement that devoted itself to the revival of zardozi to its erstwhile glory,” they remarked.

Real zardozi is handmade, with high-quality metallic threads, explained Khushi Shah, Creative Director at Shanti Banaras, while fake zardozi may look more uniform and less intricate. “Check for irregularities, examine the back of the embroidery, and purchase from a brand you trust.”

Real zardoz, no matter how heavy or intricate, will never loose its sheen and fluidity, said Dhir of Diwani Couture. (Source: The Zardos Project, Diwani Couture)

Real zardoz, no matter how heavy or intricate, will never loose its sheen and fluidity, said Dhir of Diwani Couture. (Source: The Zardos Project, Diwani Couture)

Professor Varghese explained that authentic zardozi embroidery is characterized by fine, intricate detailing and the use of high-quality materials like genuine metallic threads and embellishments that may age but not deteriorate. “True Zardozi will often have slight variations that add to its charm, whereas machine-made imitations tend to be more uniform and less detailed. Buying from craft societies and trusted sellers and brands can also reduce the risk of purchasing counterfeit zardozi.”

What can you do as a consumer?

According to Dhir of Diwani Couture, it’s not just about giant leaps, small steps matter too. “Opening up your grandma’s trunk, re-wearing mom’s saris, reviving her wedding trousseau. Just conscious choices of investing in the craft, buying from the people those who respect the craft and educating your environment on the same should be a grid enough start to support this.”

The journey to preserve a craft is a long path, there is no destination, it’s an ongoing process. The biggest problem in making zardozi has been to work with the unorganized sector, explained Dhir of Diwani Couture.

“The artisans are blessed with talent and craft but a service and product industry wants deliveries on time, more so they want relevant products and price points. Our struggles have been to sustain these artists and the craft both at the same time. To provide them livelihood, more work and support and at the same time without compromising with the “purity” of the craft and simultaneously offering the market with the relevant product,” she noted.

Zardozi embroidery is extremely elaborate, time consuming and requires the highest level of expertise to achieve the required delicacy, said Abu and Sandeep, strongly discouraging the use of cheap, machine work.

“Historically, zardozi was created using real silver and gold threads. Today copper wires coated with silver and gold polish are employed, reducing cost and weight. It is, however, still a very expensive form of embroidery due to the time and finesse required to hand embroider a garment. We definitely need to ensure that we champion the art and ensure that real hand zardozi is created that boasts remarkable quality and design,” the designer duo said.

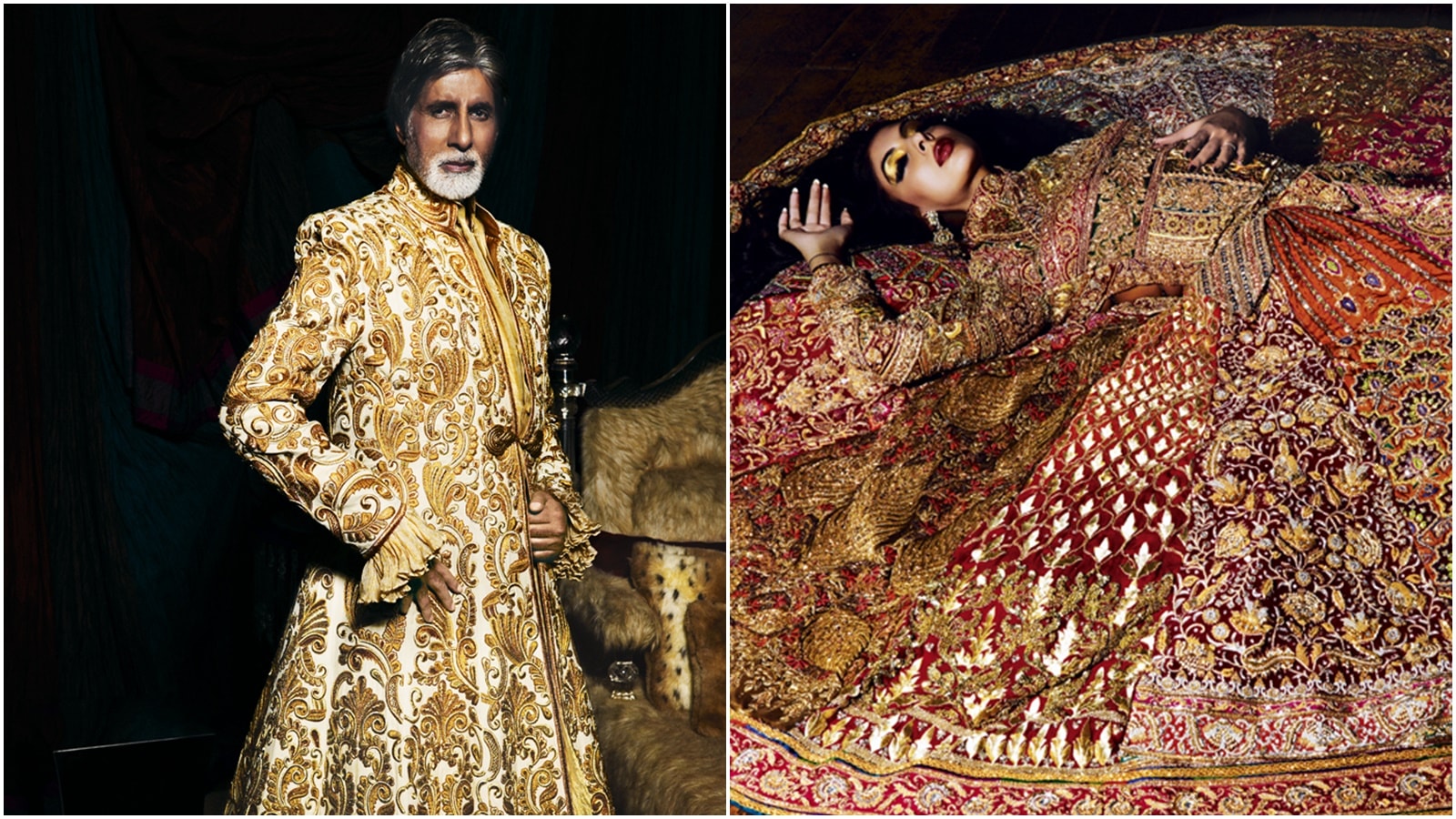

Amitabh and Shweta Bachchan in Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla for India Fantastique. (Source: Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla)

Amitabh and Shweta Bachchan in Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla for India Fantastique. (Source: Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla)

Shah from Shanti Banaras recommends supporting authentic, handmade zardozi products and buying into brands that promote both artisans and their work.

Abu and Sandeep agreed, adding that as consumers, we must embrace this craft and champion the artisans. “Machine and computer embroideries have flooded the market in recent years. We, as patrons, must recognize, value and protect art forms. We must fight for them. They are national treasures.”