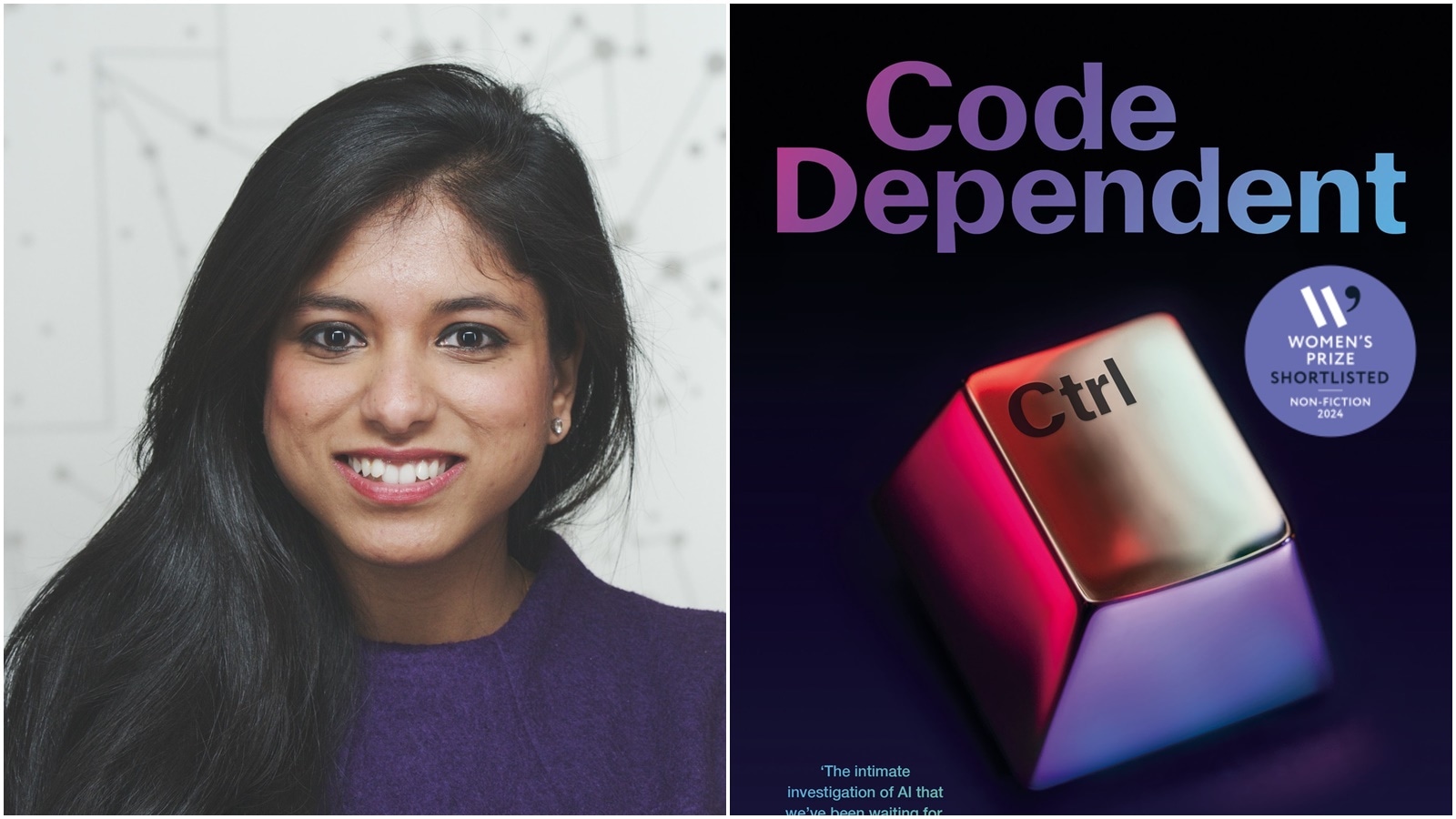

Tech journalist Madhumita Murgia’s Code Dependent (Rs 699, Pan Macmillan), recently shortlisted for the Women’s Prize 2024, collects reportage from around the world about how machine learning and statistical software — today marketed as AI — are already impacting lives and livelihoods, and not always for the better. In this interview, she speaks of the power asymmetry in Artificial Intelligence (AI), its impact on relationships and why there’s no such thing as being anonymous anymore.

Could we have changed the public perception of AI with a different label? In the book, writer Ted Chiang quotes a tweet saying AI is ‘a poor choice of words we used in 1954’.

There’s a lot of history around why it’s called ‘AI’. Apparently, at a scientific meeting in Boston, ‘cybernetics’ was the other option but people didn’t like the guy who suggested it. So they chose the alternative.

The word intelligence indicates something conscious, sentient, with some ability to reason. So far, we have none of that. This is essentially a very sophisticated statistical software. It does do some amazing things, like trawling through huge amounts of data and generating poetry and music. But it isn’t intelligent enough to make human decisions. Human intelligence isn’t just about pattern recognition. There’s emotional intelligence, social intelligence, all these other things we use while writing or being a doctor or doing social work. It involves not just the individual but the collective. AI has biases because of the data it’s trained on or because of decisions made while building. We would benefit from giving it a more direct, descriptive name that might be more boring but accurate.

I was struck by how much AI can help doctors in under-resourced places. How do you see that technology going from the private to public sector?

I write about a tuberculosis diagnostic tool made by Qure.ai. They also rolled out a Covid AI diagnostic tool in Dharavi, Maharashtra when there was no other way to test. Google has worked to diagnose diabetic retinopathy using AI and patient data. They want to help us learn but it’s a private enterprise and has to make money from it. So who’s going to step up? Are governments going to fund this? Because the people who can’t pay for regular healthcare can’t pay for AI healthcare either. It has to be subsidized and rolled out at scale.

Another challenge is: Will this create more equity? Or will there be a class system? Will you have a flawed AI system used on people who can’t afford healthcare, with mistakes that could lead to lives lost or diagnoses missed? Will people pay for human care, which can turn out to be more sophisticated?

You write about data labellers in the Global South working for American companies far away, being small parts of a huge AI-training operation, underpaid and unaware of their role. Has Big Tech tried to improve that power asymmetry?

There hasn’t been enough pressure on Big Tech to change. If there is no pressure, why should they? If they need tens of thousands of people for this job, and it’s cheaper to do it in Kenya, India or Bangladesh, why wouldn’t they carry on doing that? Big Tech can say, we’re giving people jobs they wouldn’t have otherwise had, we’re lifting people out of poverty, we’re doing a net positive for society.

Madhumita Murgia’s Code Dependent (Credit: Pan Macmillan)

Madhumita Murgia’s Code Dependent (Credit: Pan Macmillan)

Many individuals aren’t able to speak up because it’s a job supporting their families, and they don’t want to rock the boat. But now we’re seeing people who are brave enough to speak up. I mention Daniel Motong in my book, a South African migrant to Kenya, doing one of these jobs. He screened some of the worst content on social media — violence, terrorism, assault, just the worst of the internet — that he had to watch and label and mark, leaving him with lasting PTSD. He’s now suing both Meta and Sama for the impact of that job.

With media coverage, change will come, particularly around working conditions like taking more breaks, having more support, not having to sign non-disclosure agreements.

You write about public surveillance disproportionately harming marginalized communities and protesters against the state. In a country like India, how does this affect a layperson with little knowledge of AI?

Mass surveillance becomes a dragnet. You’re identifying a whole bunch of people, some of whom are just regular people going about their jobs. The argument isn’t so much that I have nothing to hide, so I have nothing to fear. What if, one day, you become what somebody defines as a persecuted minority? Those definitions change all the time. In the book, I look at a dictatorship in 1970s Latin America, where data collection became a weapon. The definition of an enemy of the state was extremely broad. It became anybody who was religious, educated, or who they felt could threaten the dictatorship. In another time, you would’ve had nothing to fear if you’re just a university lecturer. Things change under different governments. As a citizen of any country, you’re no longer a private citizen in a public space. There’s no such thing as being anonymous in a crowd anymore.

How do we advance conversations about creativity which usually begin and end with — we can generate texts so we don’t need writers, we can generate designs so we don’t need designers?

Much of the conversation is: Is this good enough for the job? That’s how tech companies are selling it. It’s good enough for your office work, to write emails, to pair programs and go play golf. It’s about convenience.

But the next step is, what if we don’t want to just be good enough? What about being the best at something? The joy of doing something? Do we want to read books written by an AI? We read books to find a connection to the author’s voice, to see something of ourselves in there. AI doesn’t have that.

Science fiction has damning things to say about how we use technology to solve social problems like loneliness. How do you see the future of this?

AI will change how we communicate. I’ve written about Renata Naira, former CEO of Tinder, and how she was disillusioned with the app changing human relationships. Now she’s working on a language-model bot offering relationship advice. She believes that it could help young people connect again by reducing the risks of putting yourself out there.

But I also spoke to researcher Ron Ivy, who says technology will lock us into cycles of just wanting to talk to tech all the time, not trusting one another. It’ll make things worse for people with extreme behaviors, like those who commit terror acts due to being lonely and shut off from the world. There will definitely be changes. I’m not fully convinced that it will be positive. I’m open to seeing where it goes.